Talking about taking research into your own hands. Mark Vink is a physician in the Netherlands who suddenly fell ill with chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). He wasn’t just your typical physician; he also happened to have a brown belt in judo, was the former captain of a Dutch national field hockey championship team and was a marathoner and triathlete.

In other words, the guy was a stud who loved to test himself physically – the last person anyone would ever expect to get ME/CFS. Or end up bed bound. Or end up using a six yard tramp from his bed to the bathroom to test his exercise capacity.

But that’s what happened. Mark Vink’s ME/CFS story – like many stories – is so striking in its suddenness and so devastating in its comprehensive that it beggars the mind to think that anyone could believe his downfall could have other than a physiological cause.

After a patient of his with pneumonia coughed in his face, Vink’s energy and endurance quickly tanked. He estimated that from one day to the next he lost 70-80% of the power in his legs. Very quickly this former marathoner was unable to walk 30 yards without having to rest for 15 minutes. He also experienced severe dizziness, headaches (for the first time in his life) and problems sleeping. Graded exercise therapy (GET) caused him to relapse further and he ended up bedridden.

For those who are wondering what psychological disasters lurked in his background – there were none. He stated he’d had a very happy childhood, had no childhood traumas, was not a perfectionist, did not suffer from anxieties and that a psychiatrist found no mental health problems. He also had no history of an autoimmune disorder, MS, pyschosis, major depression, heart disease, thyroid-related disorders or any other chronic illnesses apart from ME. He did not smoke and rarely drank.

Prior to becoming ill he was running 3-4 times a week and doing a long run of 20 to 25 km on weekends. He was probably in the upper tenth percentile in health, education and overall achievement.

All of which helped not at all when it came to getting struck down by ME/CFS. Mark’s story suggests that if you’re beating yourself up over working too hard, or not taking care of yourself you may be missing the point. Mark Vink appears to have been doing everything right and he still got very, very sick.

A Severely Ill Patient Does a Case Study of 1

Mark Vink is a not a typical ME/CFS patient. He is severely ill. It takes him twelve hours to recover from a walk from his bed to the bathroom. While he’s not typical he may not be that uncommon, though. Some estimates suggest that about 25% of ME/CFS patients are home bound or bedridden. Few ever make it into research studies.

Mark Vink obviously was never going to make it into a research study so he decided to do one himself. He did an N of 1 case study – of himself.

The “Study”

The Aerobic Energy Production and the Lactic Acid Excretion are both Impeded in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Mark Vink. Family Physician/GPwSI, Soerabaja Research Center, The Netherlands. Journal of Neurology and Neurobiology.

Noting that the pain he experienced in his legs was similar worse than he’d experienced during strenuous exercise Vink set out to capture the ‘bioenergetic” problem occurring in his muscles.

Vink measured his creatine kinase (CK), inorganic phosphate (Pi) and lactate before and after exercise. A finger prick, using pediatric sized tubes, was used to take the blood samples. The blood was then centrifuged and samples send via overnight express to the head of the Deventer Hospital Laboratory in the Netherlands.

He used a handheld blood lactate analyzer called the Edge to check his blood lactate levels frequently. The Edge was the winner in a contest of six hand held blood lactate analyzers – all of which performed reliably and accurately.

The exercise stressor he used? His 5-6 yard walk from his bed to the bathroom.

Results

Vink’s normal CK levels suggested no muscle damage had occurred and his inorganic phosphate levels were normal. His lactate levels before his little walk were normal as well, but five minutes later they were high – in fact, they were so high that Vink reported they were beyond the level at which healthy people would stop exercising.

| Patient with severe ME | 1 minute before theExercise | 5 minutes after theExercise | 30 minutes after theExercise | Std. Deviation | |

| Creatine kinase (CK) | 96 | 110 | — | 9.90 | N= – 200 U/l |

| Inorganic phosphate (Pi) | 1.45 | 1.15 | — | 0.21 | N= 0.90 – 1.50mmol/l |

| Lactic acid | 1.6 | 8.0 | 11.8 | 5.15 | N= – 2.2 mmol/l |

Minute by minute testing showed his blood lactate levels initially peaked at five minutes (as expected) and then shot up again about thirty minutes later. The thirty minute peak was completely unexpected and apparently is not found in the literature. It suggested that either

- a) Vink’s short walk had overloaded his muscle cells with so much lactate that they were still trying to dispose of it thirty minutes later or

- b) that his cells were so poor at removing lactate that even 30 minutes later they still had not gotten rid of it or

- c) both.

Vink chose thirty minutes because he’d observed that the pain and symptoms in his legs usually receded around that time. That observation was apparently explained by the large dump of lactate out of his tissues and into his bloodstream.

Vink’s findings suggest his ability to utilize his aerobic energy production system without relapse is virtually nil.

The lactate levels at the 30 minute mark were much higher, though. They higher, Vink said, than most professional athletes including marathoners reach during their most strenuous exercise efforts.

Vink attributed the high lactate levels to an almost complete breakdown of his ability to produce energy aerobically and his need to rely on anaerobic energy production. The downside of anaerobic energy production is the accumulation of hydrogen ions and lactate and metabolites that cause pain and impair muscle efficiency. Vink’s finding suggested he has an extremely small almost non-existent window of available aerobic energy production.

Using the Edge, Vink tested his blood lactate levels again and again and found that eating a meal an hour before his “exercise” (his trip to the bathroom) caused his muscle pain and weakness to last longer and delayed the “lactate dump” into the blood for another 25 minutes (55 minutes total).

Discussion

Vink’s study had an N of 1 – himself – and therefore cannot be assumed to reflect what happens in the ME/CFS community at large. It may give us an insight, however, into the exercise problems of the severely ill. People as severely ill as Vink rarely participate in research studies (and certainly never in an exercise study). While Vink’s finding of two significantly increased lactate events after trivial exercise is highly unusual, Vink’s isn’t the first highly unusual finding to show up during exercise in ME/CFS. Nor is it the first time lactate has been highlighted.

The inability of many ME/CFS patients to maintain energy levels over a two-day exercise test has been described as unprecedented by exercise physiologists. Jones’ found a jaw dropping 50 times increase in levels of acidosis (h+) in people with ME/CFS. As with Vink, Jones found that it took ME/CFS patients much longer (4 x’s longer) to clear the lactate levels from their tissues as well.

An exercise model predicted high lactate levels will occur in people with ME/CFS during exercise. A 2003 study found high lactate levels in almost 60% of ME/CFS patients after a submaximal exercise test. The study suggested that enterovirus infections were common in the high lactate producing patients. (Lane called what he found an “enterovirus related metabolic myopathy: a postviral fatigue syndrome”).

A 2005 study finding greater energy output, lactate production, oxygen uptake and heart rate in healthy controls than ME/CFS patients had an opposite finding. (Further studies, however, indicated that that study’s conclusion – that reduced effort and avoidance behavior are responsible for the reduced oxygen uptake in ME/CFS – are invalid.)

Studies finding increased brain lactate levels and D-Lactic acidosis in the guts of ME/CFS suggest that a breakdown in aerobic functioning could be system-wide.

Increased lactate levels have popped up in several comorbid disorders associated with ME/CFS as well. Increased brain lactate in a subset of GWS patients was associated with reduced exercise capacity. That finding appeared to fit well with Hue’s finding that increased muscle pH was associated with reduced cerebral blood flows in ME/CFS. Studies have found increased lactate in the brains of fibromyalgia patients and their trapezius muscles and blood and in the brains of people with migraines.

There’s little doubt that aerobic energy production is decreased in a considerable number of people with ME/CFS. Staci Stevens, an exercise physiologist, has reported that almost any activity can put very severely ill patients such as Vink into anaerobic energy production. (The first “exercise” Stevens, teaches, by the way, involves deep breathing techniques to provide maximum oxygenation of the blood without raising the heart rate.)

Some ME/CFS patients find that using aerobic testing to determine the maximum (usually very low) heart rates they should attain very helpful not just in improving their symptoms but improving their health and activity levels as well.

Heterogeneity Probably Present

The two-day exercise study findings suggest, however, that considerable heterogeneity exists in the ME/CFS population. Some people with ME/CFS may not have aerobic energy production problems while others that do have breakdowns in different aspects of their aerobic energy production pathways. My guess is that increased lactate production during exercise is probably simply one of several different energy production issues found in ME/CFS.

Conclusion

Mark Vink was a doctor, not a researcher and he writes like one. His long and at times wandering paper would not have passed muster in most journals, and in fact, it was not published in a reputable journal. (Citations from that journal, for instance, do not show up in PubMed. Citations from the now defunct Journal of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome were not found in PubMed either.)

Mark Vink may spend almost of his time bed but his case study could tell us something important about the severely ill

Vink’s do finding about himself, do however, fit what we know about ME/CFS. While Vink’s findings obviously aren’t statistically relevant for the ME/CFS population at large, his innovative approach should be lauded. Like any case study his results don’t point to a conclusion but to a possibility to be explored.

The Edge and other home monitoring tools like it present intriguing possibilities for patient centered research. Portable lactate monitoring devices appear to be fairly expensive ($3-400) but given that post-exertional malaise virtually defines ME/CFS their potential for providing insights into it could be high.

If CDC’s ME/CFS program survives the next year we should know more soon about lactate production during exercise in the next couple of years. The CDC is interested enough in the issue of lactate production during exercise in ME/CFS to be measuring it in the second phase of their large multisite study.

“The lactate levels, this time were higher, Vink said, than most professional athletes would ever reach during their most strenuous exercise. That includes marathoners which is why Vink’s demonstration demonstrates how walking with ME/CFS could be harder than a healthy person doing a marathon. According to Vink his blood lactate levels were higher than those seen in marathoners.”

This was very interesting. Before I was diagnosed I used to tell the doctors that “I feel like I’ve been running a marathon and then someone beat me up.” I have alway suspected that this is exactly what was happening with the body going into anaerobic energy production and producing lactate which then causes the extreme muscle pain.

ha ha! I always describe it as I felt like I ran a marathon and then someone ran me over with a Mack truck.

I wonder if impaired blood flow results in impaired lactate removal?

I think that’s a possibility. I think Dr. Newton is looking into it…There could be a problem, if I remember correctly, with transport mechanisms out of the cell as well. I think those are the two major candidates..

Blood flow was my thought as well, but after looking at things further it looks like an important factor is the energy-production machinery in the cells going bad. A good review article is found in:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/pdf/s12916-014-0259-2.pdf

but really this is quite technical.

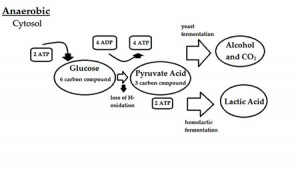

Basically it looks like there is evidence that in many cases, something damages the mitochondria (basically the power plants of the cell) and makes them less able to fully function. This would explain the lactate. Glycolysis – the first step in getting energy from glucose – happens in the cytoplasm of the cell (outside the mitochondria) and does not require oxygen. As long as things are functioning normally and oxygen is present, then after glycolysis, the remainder of the process happens in the mitochondria (and this produces about 15 times as much energy as glycolysis does by itself).

But if something prevents the processes in the mitochondria from occurring, then things stop after glycolysis and lactate is produced. Usually this happens when the cell does not have enough oxygen. But if there were damage to the pathway somewhere within the mitochondria then this could cause them to behave as if there weren’t enough oxygen despite oxygen being present.

Thanks for the explanation 🙂

With respect to Glycolysis, interestingly, my daughter finds B1 (TTP) with Magnesium helpful. A slight and temporary but useful increase in energy levels that she can use without setback.

excellent question….

This is very interesting and his findings seem to correlate with my own experience. Prior to getting sick with relapse, slow onset ME I worked out 3-4 times a weeks so I was ver familiar with the lactic acid cycle of a “normal person”. Now when I’m not in a flare and I do exercise (say 1.5 mile walk or 30 minutes gentle weight lifting) I find the lactic acid build up to be much worse and to last 3-7 days instead of 1 day.

This is all too familiar, walk up 2 steps and pain stops you going any further, on a flat surface it feels as if you are wearing deepsea divers lead boots. A researcher in Adelaide using an electron microscope found many years ago that red blood cells became malformed and blocked capilliaries during a reaction. The reduced oxygen caused the lactic acid build up and subsequent pain, yes like running a marathon but the atheletes recover in 4 hours, for me it took 5 days. The acid urine Ph escalated, obviously in the blood too.

The reduced capilliary flow caused head aches and facial pallor, any other organs affected? Logic says they must have been, no wonder ME sufferers feel so ill.

Very interesting. The first diagnosis I received in the early 90’s was McArdle’s Disease, which deals with this very issue. Might this be yet another associated issue of CF that can be named?

Surely this is a marker for ME. Many people lumped into CFS do not specifically have ME MYALGIC (muscle) ENCEPHALOPATHY – the M bit being to do with the muscles. Why of why does this article suggest this is a surprise. This is KEY with ME. This article chimes so with me. I was bed bound and then housebound and my activity levels are still very low. I was sporty and a physical therapist. I have had ME for 17 years now and still have horrendous energy/ muscle symptoms compounded by secondary symptoms i.e. ligament shortening, worn out joints, etc., and a very very limited participation in life.

I’d like to see the focus go back to the myalgic part, to the mitochondrial dysfunctions, to the build ups of lactic acid and to the longterm effects of this dysfuctions which leave so many of us in constant pain.

You know that’s a very good point because ME/CFS seems VERY muscular to me. When I exercise too much – pitifully little – my muscles feel hot and bulging and I think some sore to muscle contraction or ligament shortening must be occurring – which puts strains on the joints.

I absolutely agree with mark Vink’s study and Rosemary. I’ve always believed for myself there is a problem with lactic acid build-up and mitochondrial dysfunction.

I was also super active then crashed and yes, it certainly feels to me, like a problem with energy production in the cells, transporting sufficient O2 and the quick build-up of lactic acid which seems to take days, weeks, months to clear.

I have so many knots in my muscles, I don’t they’ve ever had a chance to un-knot in 20+ years, that it feels like I’m constantly recovering from “hitting the wall” when exercising and the recovery just doesn’t happen any more.

Its absoluty disgusting that every single person with. ME from day one of it being recognised have nit been listened to when they have described these symptoms research has been performed in this area decades ago but were never followed up because the weaselyites stole the illness. I can never forgive them for the harm and suffering they have caused the person with. ME and their families

My vo2 max results indicated very early anaerobic threshold yet my body effectively removes lactic acid according to the physiologist. Perhaps this is why I am not more severly Unwell?

Maybe! I think there are all sorts of permutations here – the end result being a bollixed energy production system.

I wonder if there is any correlation between rising lactate levels and non-restorative sleep patterns which plague me.

Me too – I would like to know the same.

My worst times for pain and exhaustion are in the mornings (although it hasn’t always been this way). I can go to bed feeling absolutely fine – almost completely normal, however I ALWAYS wake up with the ‘been run over a truck’ feeling and the pain is so bad when I first open my eyes I’m often unable to move.

My patterns don’t correlate with Vink’s findings, however, since exercise seems to LOWER my pain level – at least for a while. It seems the trick for me is getting through the first 5 min of it, which are extremely painful. I started doing this after a pain specialist at Cedars-Sinai told me to. But I also remember when I used to work out with a trainer many years ago, I would complain of muscle soreness following a work-out, he would tell me that body builders reduced their muscle soreness by ‘working through the pain’. (We were talking about next-day pain, however – which I now understand is not the same as lactic acid pain, seeing as lactic acid leaves the body within hours of exercising. Somebody put me right about this if I’m wrong!)

I also wonder if I’m just being naive about my stage of the disease. (6 yrs) It seems to me that it is a disease of stages, and that many people on this site have commented that they were able to exercise for the first few years after diagnosis, before it simply became too painful.

Great point Alice. My response is very similar. After I exercise I feel better at first – my relapse comes later. It can either occur quickly or after 24 hours depending on how much activity I’ve engaged in.

There are permutations upon permutations here. I asked Staci Stevens about this and she said lactate was tricky and there was nothing simple about this whole problem.

We obviously need some big studies…Personally if I had money this is where I would put all of it. I would have ME/CFS patients exercise and measure every aspect of mitochondrial, ANS and immune functioning I could. That would be my number one project…

Another great question!

My 15 year old daughter has suffered from CFS for three and a half years, recently she has improved, we think, by drinking a lot of water to initially try and clear her skin. On reading the above, I am wondering (as a total layman) whether oxygen taken during ‘exercise’ might help. Has anyone tried this? Or would an oxygen tent to sleep in be of any benefit?

Hi Suzy – This was my experience as well. I was a pro athlete that stopped exercising when after the onset of CFS and it got soooooo much worse. After running 1 mile one time a week and doing 1-2 days of 1 set of push ups and lunges as I went to bed, 4 years later I have gotten to where I can do 90 min workouts 3-4 times a week. I often overdo it, but I am completely functional now. I use a method of massage called gua sha which I think is the missing link in CFS treatment. But yes the graded exercise was huge for me.

So this is my experience to a T. I used to be a Pro Spartan Racer, and then all of a sudden couldn’t go shopping, couldn’t clean my house for 15 min – It was nuts. It was life changing, it was devastated. I lived for about 4 years like this (I mean it’s not gone). But I’m absolutely functional now. I went to massage school ( not knowing how I would even get through 1 massage) and learned a modality about gua sha. There’s a big long story that led me to figuring out that it worked, but I dived into research after this. Some theories about CFS center around lack of oxygen of muscles and dehydration of fascia (go ahead and grab your skin – does that hurt? It shouldn’t – if it does that usually means your fascia is dehydrated and stuck) Gua sha is amazing at helping “unstick” your dehydrated fascia. When your fascia is stuck, blood literally cannot flow through there. I would give ANYTHING to try it on this Mark.

When I started using it on myself with graded exercise therapy, I started to get better. Way better. Like I can exercise a few times a week and go on hikes and walk around an amusement park. I can massage multiple people in a day. I can move around all day. I found this article and don’t know why I felt compelled to write, but if it helps one person it will be worth it. Feel free to message me with any questions. I show the technique on my you tube channel – Zions edge massage – and you can learn to do it on yourself at home. It’s worth looking at right?

Thanks so much for sharing this information , never heard of gua sha massage before .

Suzy,

Sorry to hear about your daughter. Bad enough for us adults to be dealing with this, I can’t imagine a young kid. Good she has a Mom who’s fully engaged!

I’m a total layman also. I’ve recently been introduced to the idea of oxygen therapy so I’ve done a ‘little’ research, but I’m no expert. There might be something to this.

If the underlying cause is a pathogen, apparently they’re anaerobic creatures and can’t survive in a highly aerobic environment, so piling in the O2 has a killing effect. So there’s breathing O2, EWOT exercise with oxygen therapy, hyperbaric oxygen, and a few more. There’s also ozone therapy which is oxygen with an extra oxygen molecule added, O3, and again various ways to administer. Look for a local practitioner who does IV, O2 and Ozone therapy, a preliminary visit might be worth while.

I don’t want to raise false hope because I have no personal experience, yet. But some folks on the web claim success. Might not hurt to investigate further.

Hope this helps.

Ozone is an extremely strong oxidant that can do damage to lungs and other tissues, so the EPA sets a 75 parts per billion volume per volume limit for air.

(reference: http://www3.epa.gov/ttn/naaqs/criteria.html )

Thus, would not recommend experimenting with ozone unless you have some good reference to a careful study that shows clear benefits.

PhD Chemist, with some knowledge in air pollution

Fascinating details! Cort, again, thanks for all you do. I wonder if this doctor would be interested in the Stratton protocol which addresses c. pneumonia chronic infection? Given that he got sick following exposure to a patient with pneumonia, it might be relevant.

Then there is the point that enteroviruses can cause this. Perhaps he should try and antiviral, say Famvir??? Just thinkin”

Antibiotics helped me, but I had/have Lyme disease. I also have reactivated viruses and bacteria. Famvir seemed to help, but then I got a secondary problem and haven’t started back on the Famvir. I hope to do that asap.

This condition is so baffling. I have had steadily declining health with ME/CFS for the last 20 years, but one of my first symptoms when I was still considered normal was increased lactic acid problems related to exercise. Of course, back then all my issues were in my head. Another thing that I used to ponder back in the good old days was the feeling that my cells were not processing water correctly either. Has anyone else had that feeling or insight.

One of my first thought was lactic acid. A study agreed – then a followup study did not find that – I remember that vividly but cannot find them in PubMed.

I have the feeling this is going to be more complex than anyone ever wished….

When I exercise (which I don’t anymore because of the following), my symptom and exhaustion delay occurs the next morning at wake. Perhaps it begins while I’m sleeping and I just feel it at wake. I wake in a great deal of pain and discomfort, but it elevated several notches if I exert myself the day prior, and then begins several days of elevated symptoms.

Before CFS I exercised regularly and ran ultra marathons, plus other activities. Running would be a series of elevated exertions and then recoveries with each workout or race. I often finished feeling more relaxed and recovered than at any time during the event. Recovery is a sensation, a feeling, during and after. I would even say it has a sensation before, but I would call that an elevated exertion, something I came to expect because I was pushing myself, and then I’d expect the recovery, often encouraging it with calm breathing, meditation, or just thinking relaxing thoughts, I could bring it on sooner. I thought it was a secret magic trick. But then one day it stopped, that was 14 years ago.

Perhaps the above article helps to explain this.

Encouragement to all….

I’ve been very ill myself which means completely bedridden for years. My youngest son has the same symptoms in a light version (bad sleep, general pain, headaches, concentration issues, PEM). I fell ill during his pregnancy.

I would like to stress a point few people speak about which is glucose. He always gets PEM (physical crash) after strenuous exercise like running at school. Worse he would start vomiting if he does not get sugar right away. It is as if the body consumes glucose in a higher rate.

First we thought he was diabetic or might have some metabolic disorder but of course everything was just “fine”.

The professor gave him Fantomalt from Nutricia which is sugar for babies and infants. He doesn’t crash anymore.

It has to do with the glucose, my fifty cents.

Interesting – thanks for passing that along. Here’s some more information on fantamalt or as it’s also called Protifar

Protifar is a Food for Special Medical Purposes for use under medical supervision. Protifar is a powdered, unflavoured, high protein supplement, for the dietary management of patients with hypoproteinaemia, as a protein supplement for those unable to meet their protein requirements from normal food and drink or for patients with increased protein requirements e.g. burns, wound healing. Protifar is available in 225g re-sealable tins. Scoop holds approximately 2.5g of powder (2.2g protein).

I don’t think Fantomalt has any protein. Here is FactSheet link:

http://www.fatsecret.com/Diary.aspx?pa=fjrd&rid=2027415

It says zero protein, zero fat, 5g charbs.

I had various heart tests recently, and one comment from the doc was that I hyperventilated. I wasn’t aware of it, but maybe it’s true, given the above – and a good thing, not the bad thing he was suggesting.

I might feel good after a bit of exercise, then terrible a day or so later, and often have all-over muscle rigidity/pain. I find large doses of Vitamin C (6-8g per day) help a lot with this.

Me too. I feel the same as you do and have breathing problems too. I have more muscle weakness then pain. Vitamine C helps a lot.

I’ve been looking for answers for 29 years to the CFS/FM mystery. I used to be able to run in short races, bike, ski, and do a multitude of activities until age 32 when I became ill. No testing gave me any answers until recently (I’m hoping). Recent DNA testing shows I have significant problems with methylation AND mitochondrial function. Of the 16 mitochandrial DNA single neucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) half of them are either completely or partially blocked. Maybe this profile is common, I don’t know yet because I don’t have enough information to know if this is significant. I know that a person’s DNA is only part of the picture as to how our health manifests itself. Perhaps some of us have DNA that predisposes us to mitochondrial problems?

Tanya,

Could you tell us the name of the profile test for the 16 mitochondrial DNA SNPs that you refer to? What lab runs this test? Can I order a test kit or is it a panel any doc can order?

Thank you!

Hi Kristina,

I did a DNA saliva test through a DNA testing company (very reputable, but I think their website is difficult to maneuver) called “23andMe.” You don’t need a doctor’s order. They’ll send you the testing kit. Cost is $99 plus shipping. It takes about 6 weeks to get the results (you get them on their website). You then take that “raw data” and send it electronically to whatever company you want to interpret it. I used “LiveWello.” That cost was only about $20.

You can then print out all (there are a lot) of the DNA categories, including mitochondrial SNPs). Methylation, detoxification, clotting, mitochondria, etc. are some of them. I’m meeting a practitioner tomorrow to find out what the results actually mean. She only deals with methylation, though, not mitochondria. Feel free to email me if you would like. tkbugas@comcast.net

Hi, Cort, and thanks for this info.

I am one of the subset of people who are helped by megadoses of vitamin B1.

I read that B1 is a coenzyme for carbohydrate metabolism; putting lots into your bloodstream somehow gets the B1 to the place in your cells that doesn’t have enough to metabolize your food and give you energy – and maybe that’s how it works.

I haven’t dared get off it, because it does seem to allow me a somewhat better functionality. When I finish the novel I’m writing (Pride’s Children – which has a main character with CFS), I will experiment again, and see if the B1 is really working – or I’ve somehow paced myself slow enough to get a bit of writing done every day.

I wish someone would evaluate all these links in the energy production chain – mine sure doesn’t work.

What a fabulous little study by Vink, and so easy to do! This should at least be tried on all of us who are severely affected, as our exercise- ability is never measured. At least it would validate the group of patients who react similarly. It takes me 3-4 days to recover from minor lifting or a few metres extra walk or standing, with heavy burning and tingling, OI, etc.

What a pity the study was not published. It is so useful.

Interesting. My main problems are my trapezius getting and staying knotted up, and traveling tendonitis. I currently have thumb/wrist tendonitis – both sides, which really limits what I can do with my hands. Any studies on successful treatment of this condition? (Massage and exercise help with the trapezius issue).

So many of these energy and PEM problems now apply to me that I never had that I had to stop my morning aerobic/cardio exercise of 23 years when my FM got much worse. It seems to me I have added these symptoms I always considered to be ME. Has anyone else found that their FM has also morphed?

Just wanted to post the link to this info which I found interesting.

“Six Lies You Were Taught About Lactic Acid”

http://running.competitor.com/2014/01/training/six-lies-you-were-taught-about-lactic-acid_29432

Some good points I think were made in this and related to Cort’s posting. Sorry, but do to poor cognitive functioning I cannot explain it.

Thanks for the link!

This sounds EXACTLY like what happens to me. 50 steps or folding 3 towels produces the same burning muscles and exhaustion that a 20 mile hike over rough terrain or a really intense 5 set tennis match used to do. So how can we fix this?

I feel like there might be a wealth of information available if researchers were somehow able to coordinate with the severely ill (though I realize that’s challenging to do). Triggering a crash or intentionally straining the very sick would be immoral, but I’m sure many like me would be happy to provide test data before and after things we’re planning to do anyway.

I have no pain issues when I overdo it, but my muscles get very weak, and all of my experiences strongly suggest that my body’s energy production is malfunctioning somehow. Hopefully we’ll see more research down this path.

Thankfully much more attention is finally being paid to the severely ill. Ron Davis and the Open Medicine Foundation are doing an amazing study focused only on the severely ill and the second part of the CDC’s multisite study has a severely ill component as well. I think something is happening in England as well.

The results will be fascinating…

When I experience a “crash” it is more about being unable to move or think versus increased pain. In fact, when I am laying there, unable to tolerate movement, noise, or mental effort, I actually don’t notice any pain. I feel very peaceful, I could be dying and I don’t think I would mind too much. I get very cold and I know this is because my body temperature drops to around 96 F. Always. Every time I crash.

This is Not normal symptom exacerbation, like increased pain/fatigue/brain fog and other symptoms. A crash is a completely different experience. A crash is what makes me understand why they used to get this confused with polio. The temperature thing seems very significant to me, i think it ties in with the whole hibernation theory.

I am very interested that several commenters here had very active, athletic lives when they crashed with CFS.

Some seem to have FM as well.

I gradually came down with FM while very fit and active 23 years ago. Some of the findings and experiences re CFS are not the same with me and other FM people, but some of them are.

I certainly do suffer from fatigue but it has not been “chronic” and debilitating like with the poor people often discussed here. My problem has been pain and tightness and POTS and lack of restorative sleep.

My own experiments after learning a lot from Cort, have me believing strongly in “pacing”, and ketosis and fat-burning for energy (via low carb diet as well as pacing) to keep the post-exertion malaise to a minimum. Gradually my threshold for exertion without provoking the malaise, has risen. But it is like lifting the threshold for one’s LOW intensity, fat-burning exertion and relying entirely on that for “life”. Also, I still have the POTS type symptoms that make it impossible to do certain types of exertion for long. I mystify my acquaintances because I can bicycle impressively well but trying to even jog (let alone run) or do “burpees” or similar challenging aerobic exercises is impossible for me.

The impaired blood flows (and maybe flows of intersticial fluids as well) must be inconsistent with regard to different parts of the body; maybe I have achieved some kind of “healing” with regard to some parts of the body so far, but not others. The other things that have helped, is Qi Gong massage from a practitioner who understands FM, and a routine of stretches while immersed in a spa pool. I can now “squat” for a few seconds, which I could not do for 20 years; I started off squatting in the spa pool and gradually getting the muscles and myofascia more supple; now I can squat on dry land, so to speak. Same with quad stretches, which I can now do on dry land.

But how much of this is “coping with symptoms” versus “healing”? Have I succeeded in getting blood and fluid flows back to some parts of my body? Certainly NOT the case if I exert myself more vigorously than “fat burning” intensity level, all the old malaises come back with a vengeance if I do that. Does the body somehow over-react and squeeze off the blood vessels and intersticial fluid flows when confronted with exertion over some low threshold?

This was an interesting article, and I am curious what the doctor’s diet consisted of?Did he eat gluten and dairy, as these foods create inflammation and reduce immune function in many people. There is no mention of this with his illness.

There is an excellent resource in the US which offers a comprehensive program of supplements, diet, exercise, stress reduction and online support for Fibro/ Lymes sufferers from Dr. Bill Rawls. The vitamins are high quality and were created by Dr.Rawls an obstetrician who suffered from Fibro for many years. It is worth considering, they have been tested by my naturopath and tested very well. http://www.vitalplan.com

Interesting study, I agree little attention is paid to post-exertional malaise. Some years ago I had quite a setback when I went on an exercise bike for only 30 seconds, but when I told the doctor who’d suggested exercise what the effect was, he basically ignored it. 29 years after contracting ME – though much better than I was when I was bed-ridden – I can still land up in bed if I stand too long, walk too far, sit in one place too long ,or drive more than 3-4 miles. I also certainly agree with the person who remarked on the wretched effect this illness has, not only on the sufferer but on the family as well. How I wish there were a real cure.

My ME/CFS is now so bad, just from mental stress, that I am bedbound and housebound. I need a solution because I cannot go on like this, seriously. I have no one to help and no one who believes me and people just keep pushing me to do more and more and after all these years still don’t believe me.

Have you looked for a specialist? Cort might have some suggestions depending on where you live.